This Israeli documentary opens old wounds in the remote Lithuanian village of Polnar, where over 100,000 – mainly Jews – were murdered by the Nazis during WWII. We listen to testimonies from ageing witnesses who everyday lived with the sound of the executioner’s gunfire and the stench of rotting bodies in nearby pits. The more we hear, the more the lines of passivity and responsibility blur as we learn of the villagers’ often cold response to the nearby slaughter. However, some of the most moving memories come from those who actually escaped death by a whisker, sometimes surviving for hours, if not days, in a hellish pile of their dead and rotting relatives and comrades.

Archives

Souvenirs

The Sons of Eilaboun

On October 30, 1948, the Israeli Army marched into the northern Galilee village of Eilaboun. My uncle Badia and 18 other men from the village, who had been hiding with the rest of the village in two churches, were marched to the village square. The rest of the village residents were marched out of the village to the Lebanese border. The chosen men in the square stood waiting, hands on their heads while the Israeli soldiers huddled in discussion. An officer stepped forward, “We need three men,” the Israeli officer shouted to. Three men stood up and were marched off with the soldiers. Moments later, three shots were heard. The soldiers returned, “Three more men,” Three more shots. And so on, until only three men remained in the square, my uncle Badia among them. These three were lined up and they shot at point blank range with an automatic rifle in the square. Even now more than fifty years later my father cannot recall the incidents of that day without sobbing. He not only lost his brother, but he, and everyone in his village became refugees. When they finally returned to their village, they scarcely recognized it. Everything of value had been looted. What the soldiers could not carry off they destroyed. Sadly, the elderly residents of Eilaboun are not the only ones that repeat such stories to their children and grandchildren. The story of Eilaboun was repeated hundreds of times across the land that today is called Israel. The killing expulsion and looting of these villages was a tactic that was spelled out in a document called Plan Dalet developed by the high command of the Israeli Army to rid the future State of Israel of its Arab inhabitants, which it saw as a threat. Sons of Eilaboun tells the story of the human toll that Plan Dalet claimed on in a single one of these villages. The story is told through the mouths of the men and women who witnessed the atrocities committed on that fall day in 1948 – men and women who are determined not to let the horrors of this brutal plan be forgotten. It is a story – at times brutal, at times inspiring – that traces the struggle of the people of Eilaboun to hold onto their existence, their history, and their pride against a world that is intent to cover up the events that changed their lives forever.

My So-Called Enemy

This is the rare film about Arab-Israeli coexistence that goes far beyond documenting a one-time encounter at a peace camp; rather, it follows six of its compelling subjects for seven years to reveal the way the young women’s attitudes and relationships are tested as they mature and as the conflict deepens.

Hummus for Two

Sleeping with the Enemy/ Behind Enemy Lines

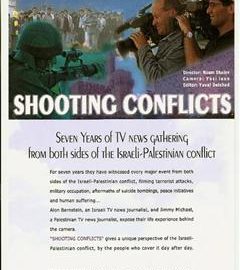

Shooting Conflicts

For seven years, Alon Bernstein, an Israeli TV news journalist working for AP, and Jimmy Michael, a Palestinian TV journalist working for BBC, have gathered the news, witnessing events from opposite sides of the conflict, filming terrorist attacks, military occupation, aftermaths of suicide bombings, peace initiatives and human suffering.

Their views and opinions are shaped and formed by personal, direct encounters with the events, undiluted by the editorial bias that dictates the daily TV news seen all over the world. In “Shooting Conflicts,” the pair reveal their first hand experiences in forthright interviews with the filmmaker.

Happy Birthday, Mr. Mograbi

How I Learned to Overcome My Fear and Love Arik Sharon

With the 1996 election campaign approaching, director Avi Mograbi set out to make a film about an infamous and admired political figure, former Israeli cabinet minister and legendary army general, Arik Sharon. To the filmmaker’s surprise, he finds Sharon extremely likeable. In the course of the campaign, Mograbi sets aside his leftist political beliefs and gets surprisingly close to Sharon. This ironic fictitious documentary tells the story of the film’s making, which turns into a domestic melodrama threaded with nightmares about Sharon and arguments with his wife. The real story is of the impossible close encounter between left and right in present-day Israel.

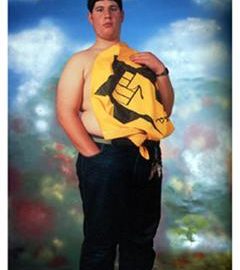

I’m a Sabra

The second of two chronological episodes dealing with the formation and evolution of Israeli identity as it is reflected in art: from “sabra” art – rich in audacity and poor in material – through the multi-cultural revolution, and up to the generation of globalization, where Place is absent. Israeli art, caught between the local and the universal.

Among the artists in this chapter are: Asad Azi, Avi Ganor, Avishai Ayal, Aviva Uri, Buki Schwartz, Danny Zakheim, David Adika, David Reeb, David Wakstein, Diti Almog, Eli Petel, Eliahu Gat, Henry Schlezniak, Ido Bar El, Joshua Neustein, Meir Gal, Menashe Kadishman, Micha Kirshner, Michael Druks, Rachel Shavit, Raffi Lavie, Said Abu Shakra, Uri Lifschitz, Yehiel Shemi.